Fire and Water

Fire and Water

Life in Spain after a year of drought

By Georgia Wingfield-Hayes

I take a favourite walk through the open meadows and wood pastures around the village where I have spent much of the last year in Sanabria, Spain, close to the northeast corner of Portugal. The thick thatch of the meadow beneath my feet crunches, an odd sensation as this land should be damp by now with a fresh flush of growth after the first autumn rains. The crunch is yet another reminder of the continuing drought. I walk past the dew pond that was full and teeming with life this time last year. Now it is completely dry with the evidence that wild boar enjoyed a wallow before the mud dried up.

This part of Spain lies on the cusp between the wet northwest and the dry central plains. The altitude here is 1000m with 2000m peaks just 20km to the north. Winters here should be cold and snowy, but last winter there was nothing blue-sky through November, December and January.

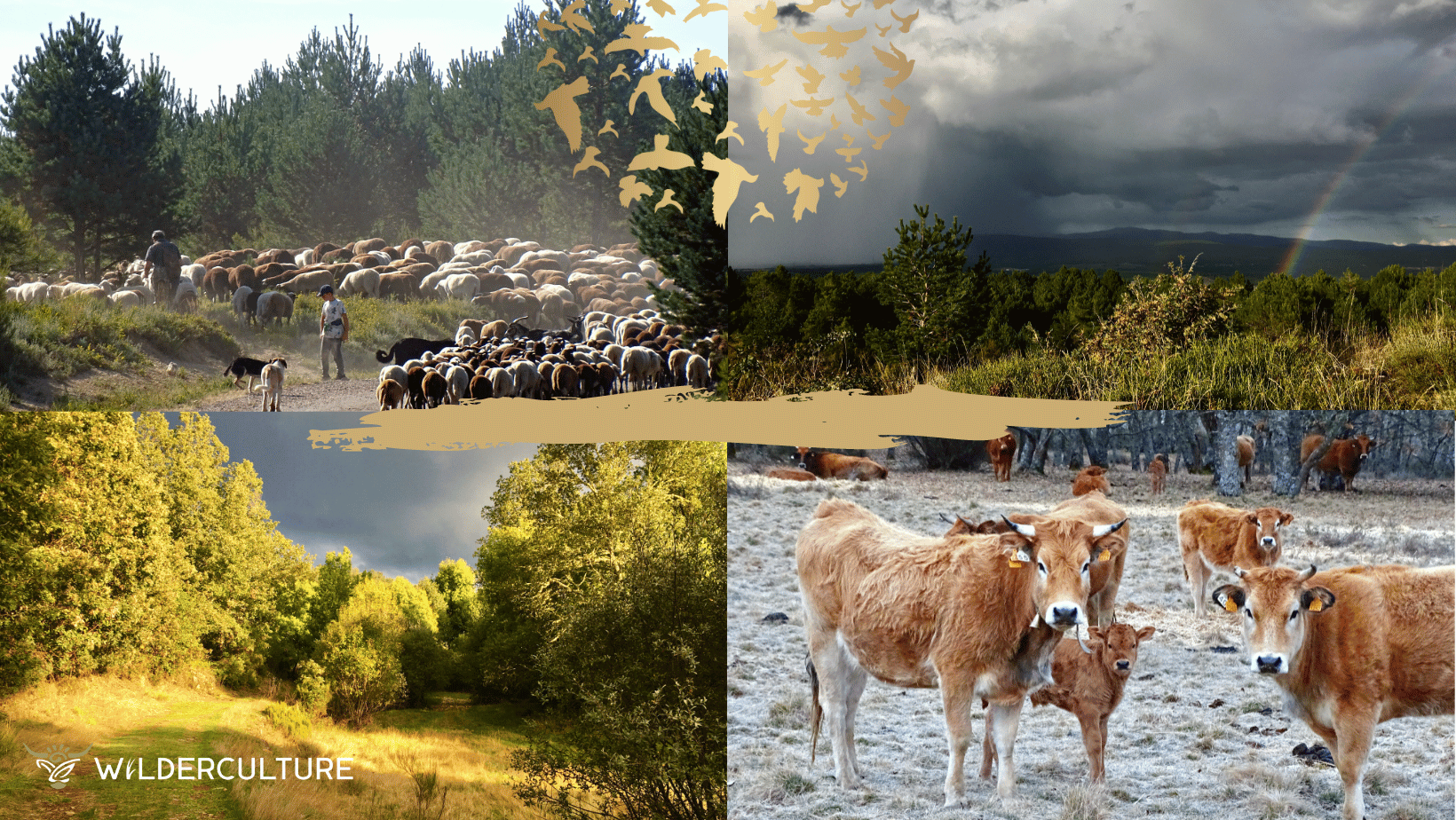

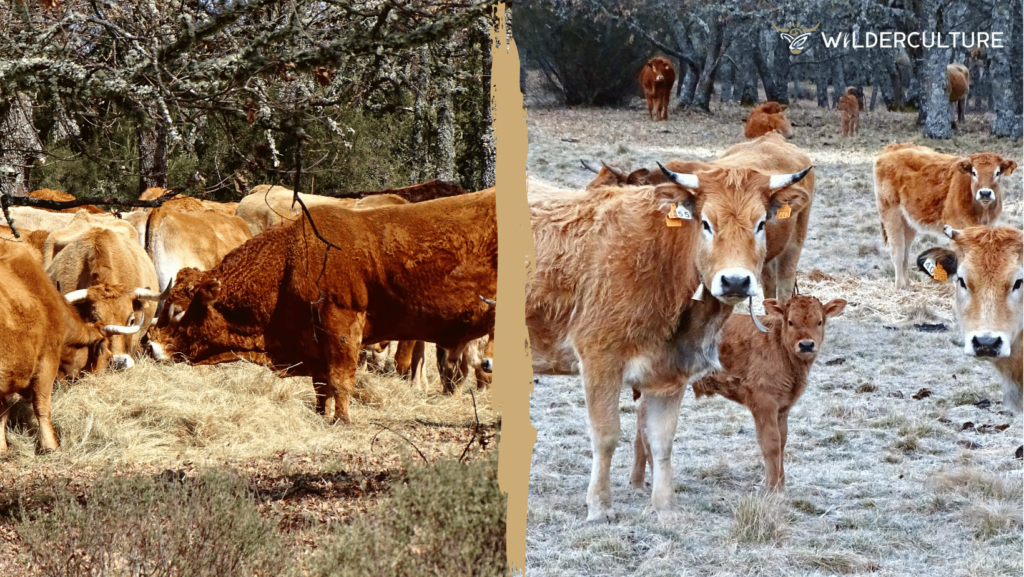

In the face of drought, this landscape is fairly resilient, being made up of a mosaic of permanent pasture, wood pasture, oak woods, pine plantation and heathland. The pastures are still managed under a traditional system, where cattle mob graze through the winter, then sheep do the same though the summer. Consequently, the soils are complex and deep as are the meadow swards.

The cattle are moved with electric fencing, but left to fend for themselves when it comes to their wild predator, the wolves. Their herd instinct and horns help protect them, as does the abundance of wild prey, so thankfully last winter no calves were taken. The sheep on the other hand, which are brought up for the summer from dryer lands to the south, are always shepherded and accompanied by a large pack of Spanish Mastiff guardian dogs. At night they corralled within the local chestnut orchards, which are protected with deer fencing.

Despite the resilience of this land, thanks to this management, I can’t help wondering what will happen if we have another year like the last. In early August, forest rangers were moving as many trout as they could from tributaries into the main Tera river, before they died in stagnating pools as the streams dried up.

This, the district of Zamora, saw 60,000 hectares of land burn between two fires within less than a month in June and July. These have been acknowledged as Spain’s worst wildfires in history. The fires burnt 29 times the land area of the volcanic eruption in La Palma, making up 73% of all land burnt across Spain this year. My neighbours and I held our breath as the first fire made its way towards us, only to have the wind change and save us from the flames.

I went to visit the aftermath of that fire in early July. It was the strangest experience walking through the oak woods of the Sierra de Culebra around Villardeciervos. It was as if the life had been sucked out of the world, rendering the landscape into sepia hues. The leaves on the oak trees were still entirely intact and soft to the touch, but instead of being green they are now a dull grey.

Highly experienced firefighters were flummoxed by the behaviour of these fires. “We knew how fire’s behaved until this year,” one forest fire veteran told me. Erratic winds within the fire made it impossible for them to predict which direction the fire would go, moment to moment. Then there were strange phenomena like lightning storms within the blaze.

One thing I can say for sure is I have never met a Spanish climate change denier.

Everyone from every class talks of it as a norm that we are living with, because, well, we are. Fires like these are deadly and fast moving because the landscape is a tinderbox and extreme hot weather seems to always be accompanied by strong winds.

I have often wondered in the last few months why it is only now, with this intense, direct experience of climate change, that the impact, psychologically and emotionally, is far more profound than I have experienced before.

Perhaps this is because I have spent much of the last year immersed in the wild nature of this place. Walking in the landscape and watching the wildlife, the birds, the red and roe deer, the wolves and wild boar. I have been learning about and getting to know these wild others and to understand their fragilities.

Wolf pups, for example, need to be close to water in their first months of life. Birds need water on a regular basis. As rivers stop flowing, I wonder what otters and water voles will do alongside all the other aquatic life. Deer like fresh lush growth so throughout August the red deer came into the village every night in search of something more succulent than they could find in the wild, an apple that had dropped early or someone’s blooming chrysanthemums.

The first fire in June in the Sierra de Culebra, couldn’t have come at a worse time. All the baby red and roe deer were still being left by their mothers during the day to sleep and keep hidden in the undergrowth. The wolf pups were less than a month old and still in the den, unable to travel. Countless animals were lost to the fire and livestock owners were left with scorched pastures with nothing for the animals to eat. Still now in October supplementary feed is being put out for the wild and domestic herbivores alike.

Beside my concern for wildlife is of course my concern for us. What happens when wells dry up? When harvests fail? The gravity of the problem is painfully apparent, yet I still feel mostly helpless as to what I can do. I resolve to travel less, buying organic food where possible and do the recycling, but it feels like the same old woefully inadequate response.

There’s one thing I have stopped doing and that is wishing for dry weather! Now when people visit and say, haven’t we been lucky with the weather, I generally decline to comment. Rain has become a blessing, the continual blue skies and heat, a curse. I recall an indigenous elder speaking of how if a community prays for something, or holds a collective intent, that there is a power in that way beyond that of the individual mind. Perhaps we could pray for rain.

As I sit here writing these final lines, I hear the tiny pitter patter of rain drops on the tiled roof above my head. I pick up my phone and look at the forecast, rain, a whole week of rain! As the drops grow heavier, I look out the window and smile as I watch this song of hope falling from the sky, rejoicing in my heart for this, water, the great giver of life.

All pictures by Georgia Wingfield Hayes.

4 Comments

richard durham 1 year ago

A lovely read Georgia, perhaps we will meet again.Richard

Caroline Grindrod 1 year ago

Thanks Richard! I hope so x

Ken 1 year ago

Wonderfully written. The first-hand account is endearingly personal and renders the urgency much more impactful. More please…!

Caroline Grindrod 1 year ago

Thank you Ken