Maximising Diversity For Profit

Maximising Diversity For Profit.

I was recently reading about some research conducted by Simon Fraser University in Brittish Columbia of farms in Alberta growing oilseed rape. They compared similar sized units and discovered that farmers who grew the crop on their entire farm would make approx. $27,000 in profit. What’s amazing and counterintuitive is that those who left a third unplanted to support pollinators like bees and other insects made $65,000. (1)

How can this be?

Modern farming has recently been heavily focused on productivity. In many businesses, you can separate the different operations and analyse them to increase efficiency which will improve financial profitability. It’s assumed that this is the case in farming too, but you can’t apply mechanistic thinking to a complex living system.

Many flowering food crops from apples and strawberries to oilseed rape require pollinators. The more habitat we can provide for these busy little helpers, the better the quality and quantity of the crop. Other creatures living in the pollinator habitat will help prevent ‘pests.’ Nature likes complex systems – they’re stable and resilient – and is always trying to add more layers and connections. When we simplify down to one crop or a couple of pasture grasses the system gets unbalanced and we see ‘plagues.’

A plague could be an overpopulation of aphids or an increase of moss and rush in your pasture. Without natural predators like earwigs and ladybirds swarms of aphids can destroy harvests and a pasture dominated by moss and rush could be drastically reducing your profitability.

Natural selection is where the most resilient individuals in a population can survive a particular environment and go on to breed. A full growing season can see five generations of aphids reproduce; that’s a lot of potential selection pressure! If you rely on pesticides to kill these annoying critters it’s not going to take long to see ‘super’ aphids with the power to overcome poisons.

In a habitat with a wide range of species, the food web becomes more complex and less likely to be ‘plagued’. Some species will thrive in the early season and enjoy more shade, some will have deep roots and like full sun, some will thrive in dry areas and some love the wet flushes. The community can adapt to changes in weather, flood, drought, cold and hot without losing available forage to pass up the food chain for herbivores then other species to eat – it’s resilient.

Not only do a wide range of species provide food security, it’s essential for keeping our livestock healthy – without medications – and for providing us with the nutrients we humans need too.

Each species of plant needs different nutrients to thrive and ward off pests. They do this by growing their roots to the preferred depth for extraction of the water and minerals they require. They take the sunlight and convert it into food – some for itself and about 40% to feed the microbes in the soil.

Why on earth would the plant give away all this food?

Because the soluble nutrients in the soil are limited, and in order to tap into the limitless source of nutrients in the crystalline structure of the rock we need to harness the soil biology.

The plant offers exudates (a mix of sugar, carbohydrates and protein) in exchange for soluble nutrients that have been accessed by bacteria and fungi from sources not available to our plant.

What’s even more interesting, is that the plant can prescribe its own medicine. (2) If the plant needs help with a disease or deficiency it can mix a cocktail of exudates that attract the organism required to provide the medicine.

These phytochemicals help the plant, but they also act as medicine for us too. (3) Wild plants contain not only minerals and vitamins but powerful drugs including; adaptogens, neuromodulators, sedatives, analgesics and psychoactives.

Native human populations understand how to make use of these important plant chemicals to maintain health, but in cultivated vegetables, we’ve bred the medicine out to make them more palatable and lost the inherent ability to heal ourselves through food. Most livestock, however – especially native breeds – still have the ability to cure many of their ailments through the selection of wild plant species – if they can find any! (4)

Maximising Diversity For Profit.

A simplistic approach may lead you to sow the highest protein yielding grasses or plants to maximise productivity. But with only one or two species in your sward, the plants are all going to be tapping into the same layer of your soil, competing for the same soluble nutrients, the same water and offering up a limited range of beneficial nutrients to your livestock.

Chicory, for example, can offer forage potential comparable with legumes and may help reduce the parasite burden in livestock. In studies on rats, it was shown to possesses anti-hepatotoxic, anti-diabetic, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, hyperglycemic and anti-ulcerogenic activities, not bad for a ‘weed.’ (5)

It’s worth knowing before you decide to ‘improve’ your pasture that the same grass plant can yield between 5% protein to 25% depending on how effectively your biology is working with that plant. Maybe it would be more cost effective to work on your soil health instead of reseeding and then being reliant on inorganic fertilisers to maintain yields. (6)

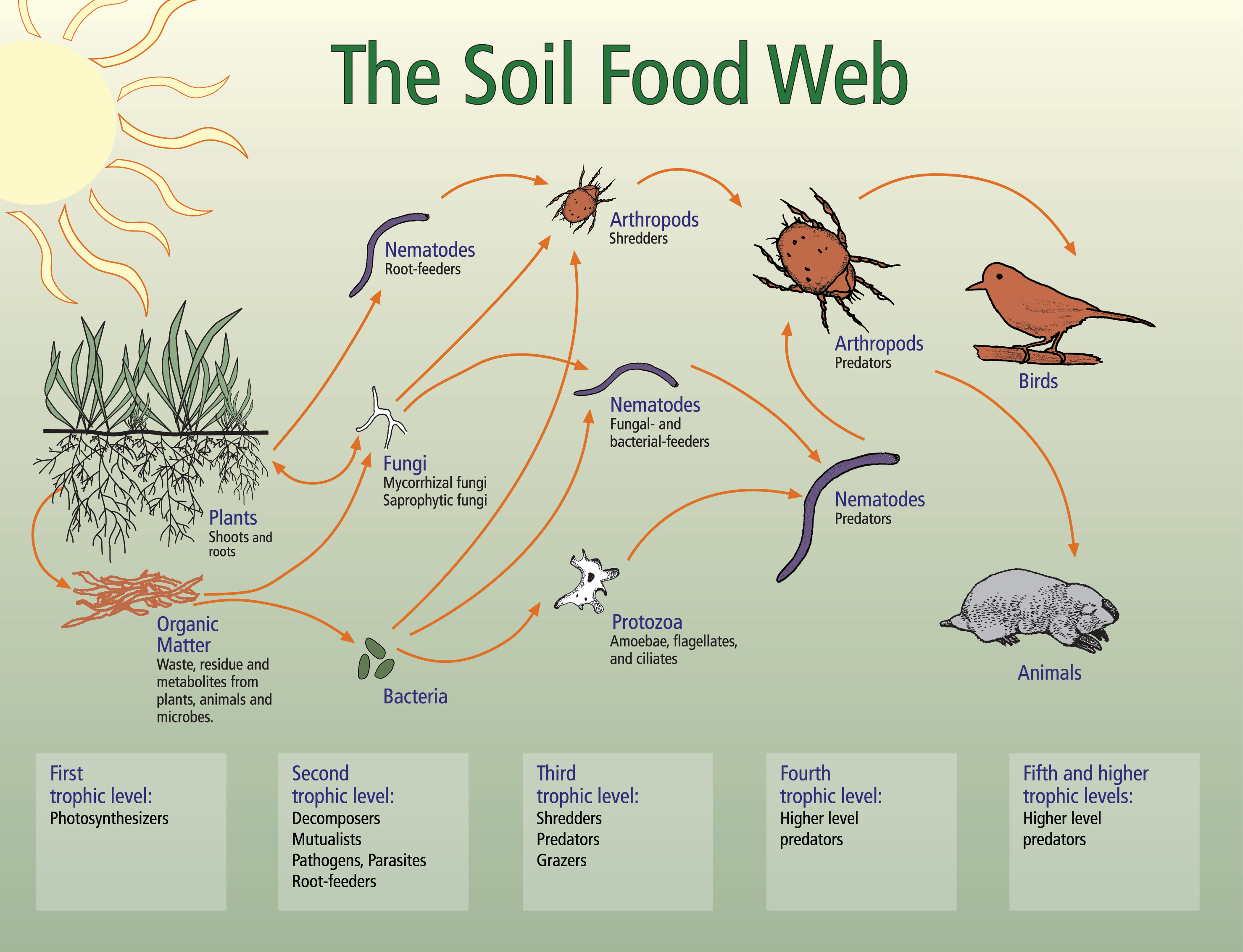

A spoonful of healthy soil contains a billion living organisms. Within the ‘soil food web,’ everybody has a job, thousands of species interact with each other in perfectly formed relationships way beyond human comprehension.

The number and diversity of these microorganisms are the key to unlocking unlimited ‘free’ fertility and drastically improving animal health. I think most livestock farmers would agree they would be considerably more profitable if they could cut out their fertiliser bill and the cost of the vet, medicines and mineral blocks.

But how can we do this?

In the beginning, as communities form on bare rock, there are relatively few species and interactions. Gradually each community paves the way for additional layers of interdependent species until you have a ‘climax’ community. This is called ‘succession’.

In habitats – like native woodland – where succession is advanced, the fertility of the soil is rich and productivity is immense – all without our help! In these soils the ratio of fungi to bacteria is high and the diversity of the overall biome is enormous.

Whether we’re managing for a rare species of flower, or for sheep production, as land managers we are trying to hold nature in a ‘state’ to prevent succession.

Maximising Diversity For Profit.

The key to maximising your profitability potential is to achieve the highest diversity possible in your underground community within the ‘state’ you are trying to manage. In wilderculture we believe we shouldn’t waste energy holding nature back, so facilitate for full succession.

It’s possible to analyse your biology through a microscope and see what species you’ve got, then use composts or mycorrhizal fungi inoculants to improve soil health – it can work. But, perhaps we could fall into another ‘reductionist’ trap of thinking we fully understand the complex interactions of microbes and manipulate it in the wrong way.

Another ‘trap’ could be assuming you need to ‘fix’ your soil ph in order to grow prefered plants. Plants are adapted to attracting microorganisms they need to protect and provide within their ‘rhizosphere’ (the area immediately surrounding the plant roots). The ph in the general field can be very high and yet give an optimal reading next to the root of the plant – the plant and its ‘team’ simply fixed the conditions.

Another – more holistic – way to build your biology is to increase the range of species you grow above ground. Each plant interacts with a different range of their preferred underground critters; the more variety of plants the more diversity in your underground army.

Holistic planned grazing, which encourages adaquate animal impact, and optomises recovery periods to encourage ALL desired species to thrive, is a tried and tested way of increasing complexity.

You can accelerate this process by introducing seed; it can work sometimes. Other times the soil biology has not yet ‘succeeded’ to the point where the microbiome can support the species you have introduced – often the case with conservation tree planting of high successional species.

Planned grazing supports a gradual shift where the whole web of life in your ecosystem is ‘on the same page.’

No Comments