Fungi and the Intra-Connected Nature of Life

Fungi and the Intra-Connected Nature of Life

By Georgia Wingfield-Hayes

Individual beings like you and me are in actuality complex communities of intra-dependent organisms. All life on earth is just one great continuum – a deeply intimate co-existence.

We often talk of the inter-connected nature of life – bees and flowers, for example, whose lives are totally interdependent. But the term ‘inter’ which means between, still suggests a separateness of each organism from the other. The flower has an edge where it begins and ends, as does the bee.

‘Intra’ means within, and as we are increasingly discovering, is a more accurate term when talking about life here on our earth. Scientists, for example, were astounded at the rate at which bees pollinating genetically modified crops, took on those modified genes into their own genome.

The gut biome of mammals consists of an extremely complex community of bacteria and other microbiota including fungi, upon which the health of the whole organism depends. An unhealthy gut biome in humans has been linked to autism, auto-immune disorders, depression and much more. Research increasingly connects alterations in the gut fungal community to inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis. Experiments show that over 100 species of fungi can be found in the oral cavity of healthy people alone.

However the place where this intra-connected nature of life is perhaps most exciting to witness (especially now that we have the visual evidence), is in the relationship between fungi and the plant kingdom.

The Fungal-Web

Fungi, as an order of beings, are deemed closer to animals than plants because they are heterotrophs – organisms that require food and can’t photosynthesis. And although such scientific segregations might be useful on the surface, they risk perpetuating our sense of organisms being separate pieces of the natural world. It would perhaps be more useful to describe fungi as the great connector, the great decomposer and recycler, the great cleanser of our world. All the time we find new uses of fungi, from cleaning oil spills, to carbon-neutral packaging and treatments for mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.

Plants and fungi have an intra-dependent relationship that goes back more than 400 million years. Some scientists uphold that the diversity of plant life on earth might never have occurred without their intimate relationship with the fungal realm.

The particular type of fungi associated with plants are those that produce mycelial. Commonly associated with forests, these fungi grow long fine tendrils (mycelia), in all directions acting as a super-connector within plant communities.

We know through carbon tracking, that food produced by one tree (say a birch) can end up sustaining another tree of a different species (say a pine) which is growing close by. In fact the more the pine tree is shaded in these experiments, the more the birch tree’s nutrients will be transferred to the pine.

This extraordinary level of cooperation and support falls outside the Darwinian notion of competition and survival of the fittest. Not only is the birch helping the pine, but that help is being orchestrated by a third party.

This brings into question the foundation of modern agronomy and forestry, and the idea that we have to minimise competition between species in order for them to thrive. Indeed it seems the opposite is true, we need to make our communities of plants and trees as complex as possible with a rich diverse soil life, so that all may thrive.

Through the Microscope

Last year scientists in Cambridge genetically modified tobacco plants, introducing 3 genes which cause a pink pigment to be produced by the plant when exposed to fungi. This allows us to see exactly how the fungal mycelia connects with the roots of plants and trees.

This visual access to intra-connected relationship between the fungi and the plant kingdom demonstrates something astonishing. Fungal mycelia don’t just connect to plant roots, but rather they enter them and go on into the whole plant.

Microscopic image of a tobacco plant root, which stains pink in the presence of fungal mycelia. Source: University of Cambridge

Fungal Mycelia Connects and Protects Plants and Trees

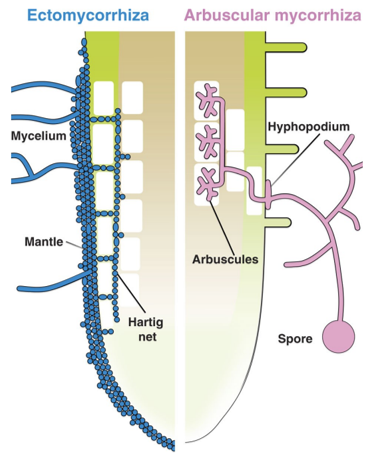

There are two broad categories of mycelia species which associate with plant roots. Arbuscular mycorrhiza are species which enter within the plant’s cells. Ectomycorrhiza species enter into the root and populate the space between the cells and around the outside of the root surface. Please see diagram below.

Source: Nature Communications

Arbuscular mycorrhiza move nutrients around the ecosystem and can enhance plant growth and photosynthesis, in particular when a plant is under stress. Almost 90% of plants, including ferns and flowering plants develop this intra-dependent relationship with Arbuscular mycorrhiza.

The Ectomycorrhiza on the other hand colonises the area around plant cells and surrounds the root tip, acting as a protective mantle to growing roots. This class of fungi also moves nutrients around and is mostly associated with the world’s forests.

This relationship of the deepest intimacy, brings into question the notion of individual species. A tree planted into soil that has been ploughed for years, with crops grown under a chemical-based system, is highly unlikely to survive due to the lack of soil life, in particular fungal mycelia.

What are the Implications of such Knowledge

It has been said that we know more about the celestial bodies that surround us in our galaxy than we do about the soil under our feet, the very organism upon which our well being and survival depends.

The simple knowledge which we have gained here, has tremendous implications for how we grow our food. For the last 100+ years we have built a chemical-based agricultural system, on the following false notions:

- That plants compete with each other for nutrients.

- The way to maximise plant growth is to feed water soluble nutrients.

- It is fine to ignore the biological function of the soil.

Knowing what we have learned here, it is easier to understand that plants grown in chemical-based systems are far more susceptible to disease because they lack the support of their vital partner – fungal mycelia.

Through deforestation, ploughing and overgrazing, we have drastically fragmented our world, above and below ground. As a result we have sick people, sick trees and food growing systems dependent on poisonous chemicals to fight an onslaught of pathogens.

At Wilderculture, much of our work is to do with helping people make the shift in mindset required to work with complexity, to work with the knowledge of the intra-dependent nature of life.

As estate managers and farmers, developing a sense of how intra-connected our ecosystems are, helps us make better decisions. It helps us understand how the tools and animal-impact and rest, for example, act upon the ecosystem below the surface, stimulating it in different ways. It helps us see that we are still only scratching the surface in terms of understanding of whole-ecosystem function, which in turn helps us step back, take time to observe and allow nature to teach us a thing or two.

1 Comment

Rodolfo Pierre G 3 years ago

Interesante apreciación Inter o Intra… Hay conceptualmente anular la separación… Un buen ejemolo Los hongos/Gracias.